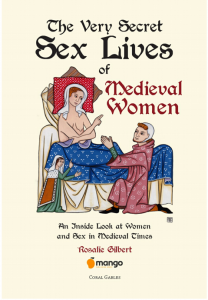

Rosalie Gilbert’s new book from Mango Press, The Very Secret Sex Lives of Medieval Women, is informative for readers new to the more private side of the Middle Ages.

Given how terrible conditions were for most women (and men) at the time, compared to the present day, it would have been easy for the author to adopt a more clinical and academic prose style. Instead, her more conversational tone, with asides, and more in the manner of tour guide, makes the topic more accessible (and a lot more witty) for the general reader.

In fourteen chapters, beautifully illustrated throughout by artist Tania Crossingham, with pictures of historical items from the author’s own collection, Gilbert covers the whole range of female sexuality from marriage, the various medicines women used to aid or avoid pregnancy, to prostitution, same sex attraction (‘Girls on Girls’ as the chapter is titled), and even how medieval society dealt with intersex persons.

|

| Rosalie Gilbert, author |

Gilbert, an Austrialian, researched hundreds of documents, including court cases, to reveal how often women got shortchanged when they went public with their grievances.

For example, women had little recourse to justice when they were subject to rape.

In court cases from 1313 to 1314 in England, Gilbert writes, “142 cases were brought against men for rape. Twenty-three went to trial and only one single case was awarded to the woman who made the charges. In the case of one Joan (of Wiltshire), who did take her case to court in 1313, it ended badly for her, as it usually did for the woman. The woman complainant is named and shamed, but to protect the defendant in question, his name is represented only by his first initial, which seems a little unfair. The Yearbook of Edward II Volume 5, recorded the case in all its complexity.”

Because poor Joan was impregnated as a result of the man’s assault, it was assumed she had consented. Why? As Gilbert points out, “Current medical thought about pregnancy was that the man and the woman both needed to climax to release seed in order for a child to form, and this only happened with the wish of both parties. Pregnancy negated unwilling sex.”

Undeterred, according to Gilbert, “some women did at least attempt to hold their attackers accountable in a court of law; they were usually met with disappointing results even if it was common knowledge that their complaints were real and the events had actually happened.”

Some women who wanted to escape the prison of a forced marriage, could avoid it by taking vows and retreating to a nunnery.

Of course, in the cloister there were lots of opportunities for women to become more than friendly with their fellow nuns. And lesbianism began to alarm the Church enough that one 11th century Decretium, which served as a manual for clergy on how to hear confessions, instructed priests on precisely how to inquire as to what kind of dildo a woman might be using for her pleasure:

Have you done what certain women are accustomed to do, that is, to make some sort of device or implement in the shape of the male member, of the size to match your desire, and you have fastened it to the area of your genitals or those of another with some form of fastenings and you have fornicated with other women or others have done with a similar instrument or another sort with you? If you have done this you shall do penance for five years on legitimate holy days.

In some places, Gilbert writes, the punishment for lesbian activity was brutal: in 1270 a set of laws passed in Orleans stated that dismemberment was recommended for actual convicted lesbians. “Should a third conviction be made by the same women,” Gilbert tells us, “what was supposedly left of her after two previous dismemberments was to be burned alive.”

As gruesome as this sounds, other aspects of women’s sexual suppression that have become stereotypes since the time, have little basis in fact. Chastity belts seem to have been a later imaginative contrivance of the Renaissance, projected back onto the Middle Ages, but Gilbert finds no examples of any that were ever imposed on the hapless wives of knights when they set off on Crusades.

While the book is devoted to the private lives of medieval women–it certainly also exposes the private lives of medieval men, not least medieval clergy who weren’t shy about ‘getting any’ when they pleased.

And while women too often had a difficult time in court filing for divorce for any number of reasons–if a man was accused of failing in the act of performing and providing a wife with children, his impotence could be tested before a group of local matrons, and if he was accounted impotent, divorce was granted.

Considering all of their trials, Medieval women did the best they could. And, as Gilbert writes at the close of her engrossing book, who can ask for more than that?

Available in trade paperback and Kindle. Highly recommended.